When Gold Hits Record Highs, the Real Question Isn’t “Should I Buy?” — It’s “Which Structure Am I Choosing?”

When gold pushes into new highs, the public narrative is usually simple: fear is rising, confidence is falling, and money is “running to safety”. That story can be directionally true, but it’s not the most useful frame for real-life decisions.

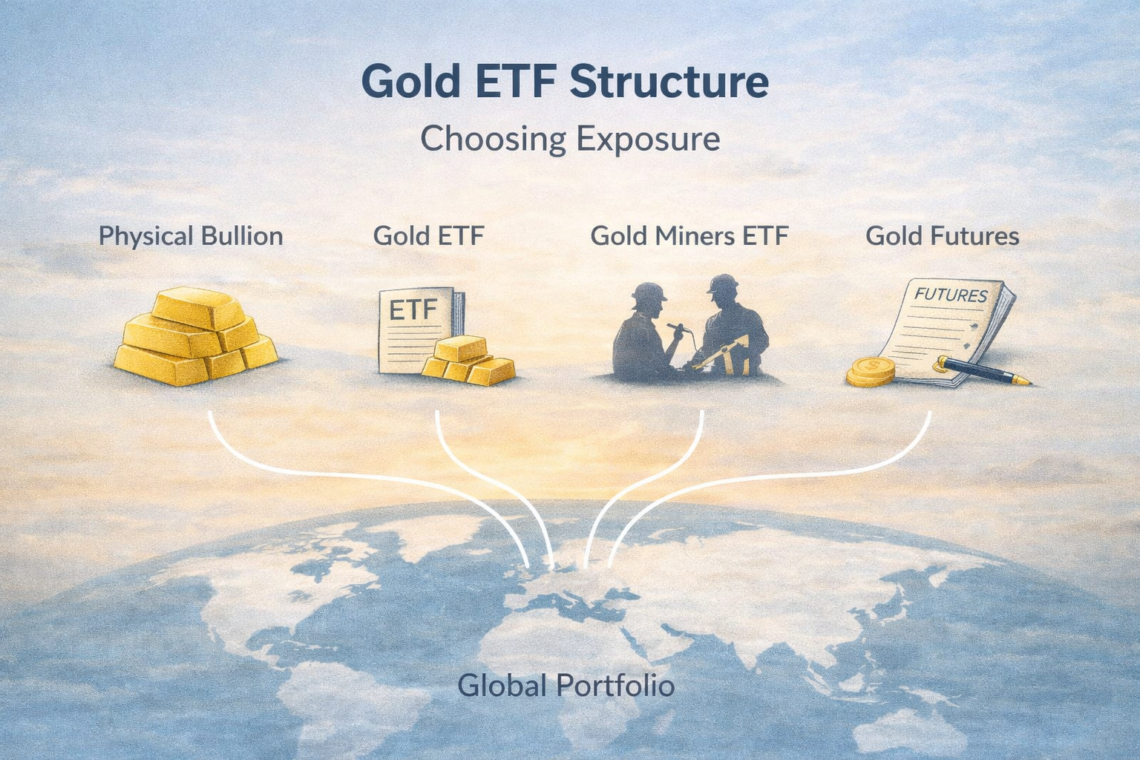

A more practical question is structural: if gold is going to sit somewhere in a long-term plan, what kind of exposure is it—an asset you hold, a claim you outsource, an equity proxy you tolerate, or a contract you manage? Those are different choices with different behaviours, even when they respond to the same headline.

What the market move actually says

Recent reporting shows gold prices breaking above $5,100 per ounce, extending a historic rally amid geopolitical uncertainty.

That price level is a data point, not a directive. What matters more is what tends to happen around these moments:

• Some investors seek insurance-like properties (crisis optionality, currency diversification).

• Others seek inflation and real-rate sensitivity (gold often responds to changes in real yields and the opportunity cost of holding a non-income asset).

• Many simply want a portfolio stabiliser that behaves differently from mainstream risk assets—sometimes, not always, and rarely on schedule.

This is where structure becomes the decision.

Structural overview: four common ways to “own” gold without owning the same thing

Below are four broad structures that investors often lump together as “gold exposure”, even though they are built on different mechanics.

1) Physical bullion: direct ownership, direct frictions

• Exposure: spot gold (minus dealer spreads).

• Return mechanism: price change only.

• Where constraints enter: storage, insurance, verification, transport, liquidity spreads during stress.

Bullion is the most literal form of ownership. It also carries the most literal logistics. There is no manager risk, but there is handling risk and ongoing friction.

2) Gold-backed ETF/ETC: outsourced custody, liquid wrapper

• Exposure: spot gold via a custodial structure.

• Return mechanism: price change minus fees (and any tracking frictions).

• Where constraints enter: fee drag, trust/custodian design, market liquidity, jurisdictional rules.

Example: iShares Gold Trust (IAU) discloses a 0.25% expense ratio and publishes net assets on its fund page. (Source: iShares/BlackRock)

This structure is often chosen for convenience and liquidity. What it gives up is the simplicity of “I hold the metal”; what it gains is tradability and operational ease.

3) Gold miners ETF: equity risk wearing a gold label

• Exposure: mining company shares, not bullion.

• Return mechanism: corporate earnings + operational leverage to gold + equity multiples.

• Where constraints enter: management execution, cost inflation, geopolitics, capital cycles, broader equity risk.

Example: VanEck’s Gold Miners UCITS ETF lists total net assets (~$4.4bn) and a 0.53% total expense ratio on its product page. (Source: VanEck)

Miners can amplify gold moves, but they also import risks that bullion does not have: balance sheets, local regulation, labour issues, and equity drawdowns that can occur even when gold is stable.

4) Gold futures: precise exposure, high responsibility

• Exposure: gold price via a derivative contract.

• Return mechanism: contract price change, shaped by margin and roll dynamics.

• Where constraints enter: leverage, margin calls, rollover costs, position management.

CME notes that each COMEX gold futures (GC) contract represents 100 troy ounces, with a smaller micro contract (MGC) representing 10 troy ounces. (Source: CME Group)

Futures can be clean exposure on paper, but psychologically and operationally they behave differently because they require ongoing management and can force decisions at the worst time.

Comparison table (structure context only)

| Vehicle (example) | Asset size (AUM) | Expense ratio | Trailing distribution yield (TTM) | Distribution frequency |

| Physical bullion | N/A | N/A (but storage/insurance costs vary) | 0% | None |

| Gold-backed ETF (IAU) | Listed on fund page (varies over time) | 0.25% | Typically 0% (non-income asset) | None |

| Gold miners UCITS ETF (VanEck) | ˜$4.4bn | 0.53% | Varies (equity distributions, if any) | Varies |

| Gold futures (GC/MGC) | N/A | N/A | 0% | None |

* Interpretation note: These figures describe structure and variability, not future outcomes. Trailing yields (where relevant) describe past income behaviour, not promises, and many “gold” structures are fundamentally non-income by design.

What the numbers do not show

1) Path dependency (how timing changes lived experience)

Gold-backed funds and bullion can feel similar in calm markets. In stress, the lived experience can diverge: dealer spreads widen, liquidity behaves differently, and “access” matters as much as “price”.

2) Behavioural load (how much the structure asks of the holder)

A structure that demands frequent monitoring (futures, highly volatile miners) can create a hidden cost: forced attention. That cost is not on a fee line, but it shows up as decision fatigue and bad timing.

3) Hidden correlation (what you actually become exposed to)

Miners are often treated like “gold with leverage”. In practice, they can behave like cyclical equities at exactly the moment bullion is acting like insurance. The label stays the same; the correlation does not.

Portfolio-level framing: fit, not optimisation

Gold usually enters portfolios for one of three roles:

• Diversifier: a different return driver than mainstream growth assets.

• Insurance-like optionality: a form of resilience when confidence in systems weakens.

• Regime hedge: sensitivity to real rates, currency shifts, and geopolitical risk.

Each role pairs differently with the four structures. A person who wants “low-maintenance diversification” is choosing a different shape of exposure than someone who wants “high-conviction tactical expression”. The relevant question is not efficiency, but fit—how a structure behaves when conditions change, and whether it expands or constrains future choices across a global portfolio.

Calcufinder context: planning inputs, not decisions

Gold becomes easier to think about when it is treated as an assumption, not a bet. In practice, the useful inputs tend to be things like:

• how stable (or unstable) the income side of a plan is,

• how much volatility a portfolio can absorb without forcing behaviour,

• and what role “non-income assets” play next to cash flow.

These are the kinds of inputs that become clearer under different income and volatility assumptions, not because the future can be predicted, but because constraints can be named.

A grounded closing perspective

Gold making headlines is not unusual. What’s easy to miss is that the same headline can justify four very different structures—each with its own frictions, risks, and behavioural demands.

In the long run, the most durable investing decisions tend to be the ones where the structure matches the life it has to serve. When conditions change—and they always do—structure is what remains after the story fades.

Disclaimer: This article is for general information only and is not financial advice. You are responsible for your own financial decisions.